November 1 will mark 4 years since our move to LA and the rechristening of this blog. I feel like the sheer amount of what’s happened, personally and just generally, since 2019 served almost as a paralytic in terms of writing here. Worldwide calamity, personal loss. It was enough to simply live, survive and, where possible, find moments to thrive. But our upcoming “Cali-versary” on November 1 made me think again about renewing this space. Bear with me, please, as I lubricate the gears and get the words flowing again.

Zagging when most zig: It was an interesting time to move to California. Fall 2019, as movers were loading up the packed boxes of our belongings to make the trip west, the driver told me that that year he had 15 trips out of California to Texas — and only one the other direction. I suppose our household was the second.

The migration to Texas isn’t necessarily new. I’ve personally seen it happen since the ’90s when the sleepy town I went to college in became a globally known tech hub populated by Silicon Valley refugees. Last June, The Economist devoted a special report to why Californians are leaving for the Lone Star State. There is a lot of crowing in Texas about all the migrants fleeing their “high-tax” homelands, but as a once-professional observer of the Texas economy, I’ll just say that there is something to the adage that you get (or will get) what you pay for.

It feels about right, anyway, me heading in the opposite direction of the zeitgeist. Yes, California is expensive; there are wildfires and earthquakes and mudslides (oh, my!). But it’s also an economic juggernaut, a creative firepower and, simply, one of the world’s most beautiful places. J and I were and are excited about making our home here and exploring the Golden State’s many bounties.

Spending the pandemic in downtown Los Angeles: Like in a lot of cities, LA’s downtown has undergone a revitalization in the last 15 years. Old movie theatres and department stores along the district’s original corridors are being renovated into (very expensive) loft apartments and the opening of LA Live, a sports-and-entertainment complex, boosted construction in what was rechristened “South Park.”

That’s where we moved in on New Year’s Eve day 2019. For a couple of months, I walked to work (about a mile) to the Bunker Hill neighborhood and we lived the urban life, walking to restaurants and grocery stores and going to museums and theatre. Four major highways come together downtown, giving us an easy on-ramp to explore the various parts of the region. Of course, we all know what happened in March 2020.

As quick as you can say “lockdown,” all that activity vanished. In fact, my company, which has offices in Asia, was an early monitor of the virus and sent us home, even before the state did, in late February. For the first six weeks of lockdown, I didn’t even leave our apartment, much thanks to essential workers who enabled delivery of groceries and other supplies.

Downtown didn’t really lend itself to the pandemic bubbles many people formed in their neighborhoods so, save for the occasional dog walker spotted in the distance, our world shrank to the two of us and Beckett. We were able to have socially-distanced picnics with our friend Allison Levine, who was a cherished social lifeline, but mostly we took day trips all around the region, along the coast from Coronado Island to Santa Barbara, inland to Riverside and the Cleveland National Forest.

With very few people out on the highways, we made really good time. The Santa Monica pier, door-to-door, took 10 minutes — an experience I’m sure we will never again be able to replicate. We had lots of time to work on home projects, revamp the space formerly known as guest room into home office/gym with the purchase of a treadmill, and to cook (and eat) a lot.

It was weird to have hit pause on life for two years but we know we were and are fortunate. We got our COVID vaccines and boosters and avoided getting COVID until a year ago when James got it and then until this past May when it finally got me. Thankful that there are no lingering symptoms for either of us, though, my extra gift with purchase was shingles and I cannot say this loud enough: You do NOT want this. Go get your shingles shot right now.

Finding community: In the last 18 months life has returned to a more-or-less normal. We’re both back in the office part of the week; it was remarkable how quickly I went from having a mask with me always to not now knowing where any are if I needed them. We moved last summer to a condo near UCLA and, even though I now have a bone fide LA commute, I love the neighborhood. Still walkable, Westwood Avenue and Santa Monica Boulevard have tons of restaurants and grocery stores just a few blocks away, but leafy and quiet once you step into the neighborhood.

One meaningful way I’m getting to know my new city is through the Junior League of Los Angeles for which I’m in my second year as Sustaining VP. We’re two years away from celebrating the 100th anniversary of our founding here and it’s been a pleasure to work with the 800 smart, dedicated and kind women in this group to help make LA a better place to live. Our focus is parterning with community organizations doing work in foster youth, food insecurity, children’s health, mental health, housing, education, literacy, public health crises, human trafficking, and domestic violence.

LA is a big city and JLLA makes it a bit smaller. I really missed the social connection of friends during the pandemic and JLLA has been a big way to fill that gap.

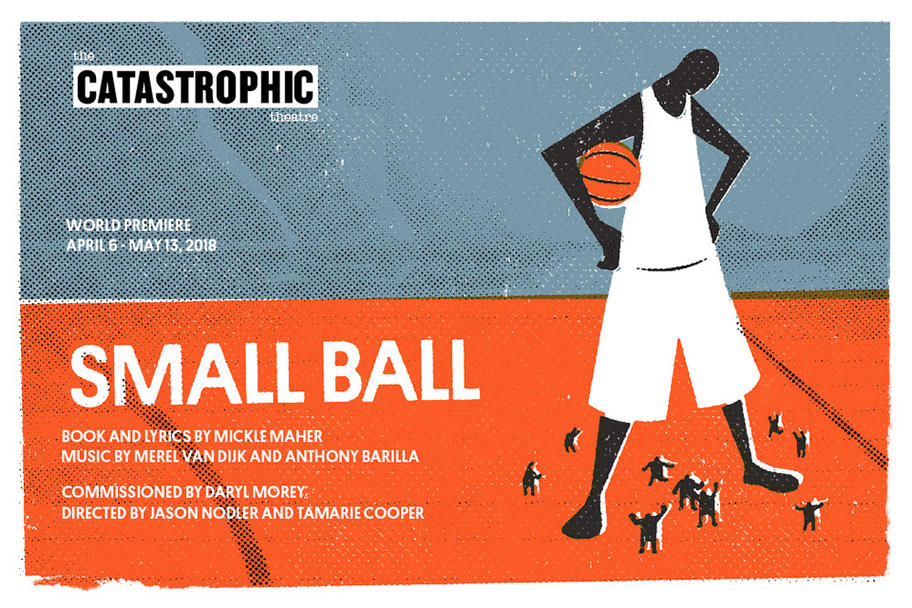

One of the things that I admire about Catastrophic is our “pay what you can” ticketing program. We want art to be accessible to everyone — regardless of ability to pay. Our suggested ticket price is $40 but someone can “buy” tickets for $0 if they really can’t afford it. Luckily, we also have a number of ticket-buyers who pay much more than that suggested price. Together, we’re building a unique theatre community both within and without Catastrophic.

One of the things that I admire about Catastrophic is our “pay what you can” ticketing program. We want art to be accessible to everyone — regardless of ability to pay. Our suggested ticket price is $40 but someone can “buy” tickets for $0 if they really can’t afford it. Luckily, we also have a number of ticket-buyers who pay much more than that suggested price. Together, we’re building a unique theatre community both within and without Catastrophic.